In the 2016 filmArrival, a linguist must figure out how to communicate with enormous seven-limbed aliens, starting with no shared language at all. Her first trembling, breathless attempt to bridge the communicative gap sees her pointing at herself, trying to convey the meaning of the word “human.”

The aliens seem to understand. This sets them apart from every non-human species on our planet: there’s currently no evidence that even our closest primate relatives can figure out what a new communicative signal means just from context. It’s an ability we humans take for granted, but it’s clearly not trivial at all. This ability intrigues evolutionary linguists, who are trying to piece together a picture of how language may have arisen.

A paper in PNAS this week reports a new part of that picture: four- and six-year-old children are capable of communicating with each other even when they can’t rely on language. What’s more, their communication quickly develops some of the core properties that define language. It’s a finding that fits in well with other research on language evolution, and it helps to explain a little bit more about how humans may have developed our wild and wonderful communication system.

Let there be language

Many of the thousands of currently living languages have ancient roots—we can trace them back through centuries of previous forms. But some languages are brand new, like Nicaraguan Sign Language (NSL), which emerged in the 1970s. Until this point, deaf people in Nicaragua had been isolated, with no opportunity to learn or develop a shared language. When deaf children were finally brought together at a school, a new language began to emerge—and unlike Arabic, Mandarin, or Zulu, linguists were there to study its emergence. Research has tracked how NSL has changed during the time from the first generation of signers to its current iteration, developing shared properties with other languages along the way.

But the researchers weren’t actuallytherein the playground when the children first met and began to communicate with each other,Arrival-style. What did that look like? How did they make themselves understood before they shared a language? And how do those first few pantomime-like gestures transform into actual language, conveying an infinite array of concepts?

Some of these gaps can be partly filled in by evidence from lab experiments that have people play various communication games while we observe the outcomes. Many of these experiments use silent gestures: they take hearing participants with no knowledge of any sign language and have them play a game that involves communicating without speaking. These tasks have shown that people have little difficulty communicating and that their gestures quickly take on language-like traits.

But the vast majority of this work has been done in adults, and that leaves a big question: do children have the same abilities, and when do they develop them? That’s a critical question for understanding what the origins of a new language would look like.

博翰曼努埃尔和他的同事们图d out a way of doing a silent gesture experiment with kids: by putting the kids in separate rooms connected by a video feed with no audio, they forced the German-speaking kids to gesture to each other rather than speak.

Emerging grammar

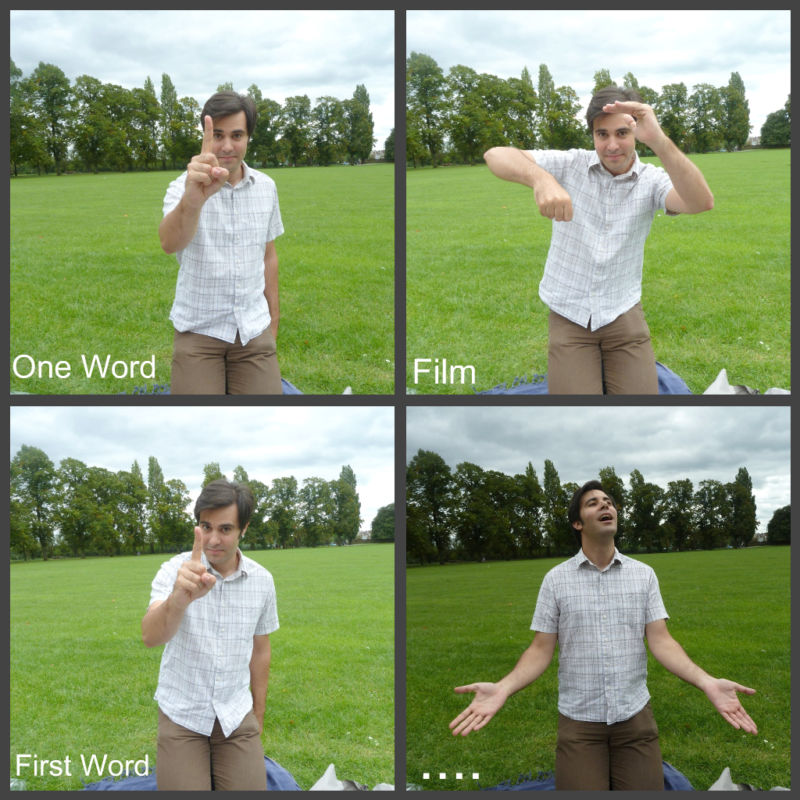

The children had to play a game similar to charades. One of them had to convey a meaning, like “bicycle” to their partner, who then had to choose the correct picture from an array. The kids weren’t told to gesture—they were just told to communicate and placed in a situation where speech wasn’t an option.

The very youngest children, who were four years old, had to be prompted to use gestures. But six-year-old kids figured it out quickly on their own and played the game with each other with high levels of success.

The same pictures came up repeatedly throughout the game. This gave the researchers the chance to see what happened when the kids had to refer to the same concept over and over again. They found that the children quickly developed conventions, with their gestures bearing less obvious resemblance to the ideas they were trying to communicate.

In one pair, Bohn says, the child had the tricky task of communicating a blank white space—the idea of “nothing.” After a few failed attempts, she noticed a white spot on her shirt and pulled her t-shirt to the side, pointing to the spot. Her trick worked, and her partner guessed correctly.

In the next round, when the blank image came up again, the other child pulled her shirt to the side and pointed to it—even though her shirt had no white spot. In a single round, the gesture had gone from being tangibly linked to the concept of “nothing” to being completely divorced from it. An outsider looking in wouldn’t be able to figure out what the gesture meant by looking at it—just like in real languages, where no one can figure out what “elephant” means just from the shape of the word.

在以后的实验中,六,八岁的气ldren also started to develop mini-grammars by establishing “words” that they could combine in different ways. For instance, instead of gesturing “a big duck” by using the “duck” gesture with bigger movements, they developed a sign for “big” that they could use with a range of different words. When they combined gestures, they didn’t stick to German word order, which suggests a limit to how much their native language was coming into play.

Later generations

This method did a great job in overcoming some of the difficulties that come along with research on kids, says Limor Raviv, a linguist who wasn’t involved in this research. And it’s timely work, she adds, coming at a point where evolutionary linguistics—a relatively young field—has a lot of questions and claims about the abilities of children.

It would be great to see replications with kids from other backgrounds, she says. And it's important to think about the role that linguistic experience may have played in the results, she adds. Even young children already have years of being exposed to language, including conventional gestures for concepts like "drink" and "big," so this isn't a perfect test case for children who have no language exposure at all. But showing that young children have the ability to figure out new signals, and that their gestures develop language-like traits, helps to fill in an important gap in the current literature, she says.

Bohn emphasizes that the research isn’t making any actual claims about what happened in the early days of language in our species—there would be a lot of inferential leaps to get there, and evolutionary linguistics doesn’t have the luxury of all the evidence it would need to make them. But understanding the abilities of children gets one step closer to a complete picture of how modern humans can create a language from thin air.

PNAS, 2018年。DOI:10.1073/pnas.1904871116(About DOIs).

You mustlogin or create an accountto comment.